Food for Thought: Austen’s letter 153

The “food for thought” is a new reading of a simple sentence in Letter 153 of Jane Austen’s Letters.

While breakfasting today, I pulled out van Ostade’s book In Search of Jane Austen at the point of my bookmark – page 88. As typical with me, although I had read past the point, my eye drifted towards the early paragraph (but not at the TOP of the page) on the left-hand page. She writes,

“Only a few spelling errors went uncorrected [i.e., demonstrated or endnoted in Le Faye’s editions] — visitted in letter 37, to for too in letter 73 [I may have spotted another one of these], and a fine lines for a few lines in letter 153….”

This LAST one I REALLY wanted to see for myself; I pulled out Modert.

One thing I have learned to do is to really look at the strokes comprising a word. The worst is someone’s name; the ability to puzzle out the MEANING sometimes helps to puzzle out the contentious word. Still, there are times when NO sense can be made of the strokes the pen has made. Let’s face it, there are times that “we” simply don’t spell or make enough “lumps” and the word LOOKS incorrect or not like it should. It’s a crap-shoot, at times, when transcribing handwritten text.

You really are COMPARING the letters in the “unreadable” word with the letters of other words. “How does the writer form letter [such-and-such]?” Conversely, if you think you know what the word should be or have no clue – look to see if that same WORD is present elsewhere. Other sentences might help make sense of that word.

This one — the “few” (transcribed in Le Faye) or the “fine” that van Ostade detected — definitely does NOT look like few. The word DOES begin with “f”; it looks to end with “e”. But I come up with something different from either Le Faye OR van Ostade.

The word looks to be “five“.

I believe we see Austen in the midst of thinking up a comic jab.

The words in Le Faye:

“As to making any adequate return for such a Letter as yours my dearest Fanny, it is absolutely impossible; if I were to labour at it all the rest of my Life & live to the age of Methusalah, I could never accomplish anything so long & so perfect; but I cannot let William go without a few Lines of acknowledgement & reply.”

To justify the lines as they appear in the holograph:

“As to making any adequate return for such a Letter

as yours my dearest Fanny, it is absolutely impossible;

if I were to labour at it all the rest of my Life &

live to the age of Methusalah, I could never accomplish

anything so long & so perfect; but I cannot let William

go without a few Lines of acknowledgement & reply.—“

An Aside: It is interesting to SEE that in the small words that end in “t”, (“it” – “at” – “let”), Austen does not cross the “t”. This differs from double-t’s (“letter”) and longer words that end in “t” (“without”, “cannot”).

But back to the word “five“:

Beginning in the middle of the line, Austen moves from the obligatory (highly elaborate) PRAISES of Fanny’s own letter. Was this letter carried from Fanny Knight to Aunt Jane by brother William Knight? Had it come through the mail? Unfortunately, the holograph of Fanny’s letter is missing. However, the phrase “I cannot let William go without….” sounds like his visit was one that would see him leave Chawton for home (Godmersham) and be the expedient conduit for her answer to Fanny’s letter.

It would be natural for a writer to say, I cannot let this person depart without “a few lines of reply”. But this was JANE AUSTEN, who already wrote with her tongue firmly in cheek (who else would internalize Methusalah!?!). With mind racing ahead, she began to write the standard phrase “I cannot let William go without a reply”. Instead, came the idea that she had written “five Lines of acknowledgement”. In a hurry and without re-reading the letter (as people sometimes would do), the word “a” before “five” did NOT get scratched out nor relocated (inserted) to just before the word “reply”.

But isn’t it a true Austenian comment, to joke, “I cannot … go without FIVE Lines of acknowledgement“, which Fanny would well have understood.

Compare for yourself by locating on the above letter snippet Austen’s other uses of “n” – “w” – and “v”.

In Vindication of Cassandra Austen: UPDATE No. 1

My December 16, 2023 blog post announced the book I am currently writing: In Vindication of Cassandra Austen: How Jane Austen’s Sister Saved a Legacy, but Lost her Reputation. I supply the link, in case, Dear Reader, you are not reading the blog in chronological order (it is the previous post).

I have quite gotten out of the habit of blogging about WHAT I AM DOING. The “finds” that used to happen are fewer and some things I just won’t talk about (or show) online. Yet, today, I have been enjoying the minutiae of letter transcription – and think to share a few “thoughts”.

The book I am currently going through with a fine-tooth comb is In Search of Jane Austen: The Language of the Letters, by Ingrid Tieken-Boon Van Ostade.

When I first found this book last year – for it is nearly 10 years old (Oxford University Press, 2014), I was overjoyed to find her findings confirming my own. She bases her expertise on her work with Robert Lowth’s letters; you can guess that my “expertise” comes from the massive Smith and Gosling Family cache of letters with which I have lived since 2007.

Some readers will find her information too esoteric. Van Ostade studies letters with a linguist’s eye. She cites her findings and aims readers backwards or forwards, reminding us of something discussed or what she will be discussing. Among the minutiae, however, comes the TINY bits of information that anyone sifting through Jane Austen’s letters needs to tease out or have pointed out. Today’s “read” chapter looks at (among other things) corrections and excisions and additions. Van Ostade points the way (for those with the books to hand) to the relevant sections of Le Faye’s Jane Austen’s Letters (2004 and 2011 editions) as well as the facsimiles in Modert’s book, Jane Austen’s Manuscript Letters in Facsimile (1990).

I have noticed, among differences between Le Faye’s 3rd and 4th editions, that the 4th ed. typically jettisoned the exact thing that _I_ would follow up on: the original publications for short, pertinent discussion of small “finds” by various authors (sometimes printed in JAS’s Reports; sometimes in Notes & Queries – which was Le Faye’s own favorite place of publication). As the 4th edition grew and grew, to lose these “original” thoughts was just the wrong thing to delete. (Type got smaller too.) This is where the annotated section of Jo Modert is especially useful, for her scholarship predates the 3rd Le Faye edition of Letters. Van Ostade mentioned on excision that was NOT included in the transcript by Le Faye. A small point, though, as I always strike out x’ed out word(s), I appreciated the attention to detail. — For _I_ would never sit with the TWO books – reading the letters and checking the transcription. Hard enough to do that with my own research – but at least there I have the image on the screen AND the typescript right beside it.

I am currently trying to find the whereabouts of several JANE AUSTEN letters sold recently – for instance, at auction in 2017 and 2019. One large fragment (dating to 29 Nov 1814; written to niece Anna) Sotheby’s sold to the Jane Austen House Museum. Obviously, letters that are in archives are fairly “stable”; i.e., we know where to find them. (Thank Goodness!!) IF YOU KNOW the whereabouts of letters, do leave a comment or get in touch.

In Vindication of Cassandra

Today, on Jane Austen’s birthday – 248 years ago; and in the year that celebrated Cassandra Austen’s 250th Anniversary of her birth (January of 2023), I announce an upcoming project, which (hopefully) will see the light of day in the celebratory year of 2025:

The project is entitled, In Vindication of Cassandra Austen: How Jane Austen’s Sister Saved a Legacy, but Lost her Reputation. Based on my investigation into the (extant) familial correspondence of the Smith and Gosling family networks, this book will redress Cassandra Austen’s significance as collector of her sister’s epistolary legacy. No more “Cassandra the Destroyer”! Every notice of an Jane Austen letter – whether up for sale at auction or merely up for discussion, claims that BUT FOR CASSANDRA “posterity” would have MORE Jane Austen letters. In truth, BUT FOR CASSANDRA “posterity” would have hardly ANY Jane Austen letters.

In redressing the situation, I show how letters, among the Smiths and Goslings, were saved (yes, they are my “case study”); by whom; and how many – per recipient, per author. It is an illuminating study. (If I say so myself…) In Vindication of Cassandra Austen looks at the correspondence circle around the two Austen sisters – noting what once survived as well as what survives today. I also postulate upon HOW any new information should most likely turn up. as – and it isn’t, per se, new Jane Austen Letters (snippets on the other hand ARE possible). And also why identification may prove a bit hard, even in this age of digitization.

In Vindication of Cassandra Austen is a major study of Austen familial correspondence and the significance of the Legacy left by Cassandra Austen.

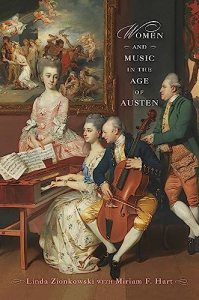

Now Available: Women & Music in the Age of Austen (book)

It is with GREAT pleasure that I announce the publication – released on 15 December 2023 (in time for Christmas gifting) of our book, Women and Music in the Age of Austen (Bucknell University Press).

A couple of weeks ago I received my copy of the book:

The first time of seeing everyone’s essays, this day’s mail, long awaited, ended up being quite exciting. Part of the series “Transits: Literature, Thought & Culture, 1650-1850,” here is Bucknell’s description of our collection:

“Women and Music in the Age of Austen highlights the central role women played in musical performance, composition, reception, and representation, and analyzes its formative and lasting effect on Georgian culture. This interdisciplinary collection of essays from musicology, literary studies, and gender studies challenges the conventional historical categories that marginalize women’s experience from Austen’s time. Contesting the distinctions between professional and amateur musicians, public and domestic sites of musical production, and performers and composers of music, the contributors reveal how women’s widespread involvement in the Georgian musical scene allowed for self-expression, artistic influence, and access to communities that transcended the boundaries of gender, class, and nationality. This volume’s breadth of focus advances our understanding of a period that witnessed a musical flourishing, much of it animated by female hands and voices.

Published by Bucknell University Press. Distributed worldwide by Rutgers University Press.”

Here are the chapters, to tempt you, Dear Reader, into taking a look at the book:

Illustrations

Table

Acknowledgements

Abbreviations

Introduction: “It was all in harmony”: Musical Women in Austen’s Culture

Linda Zionkowski with Miriam F. Hart [our esteemed EDITORS]

Part I: Representing the Female Performer

Chapter 1: A Musical Room of Her Own: Musical Spaces in Jane Austen’s Novels

Pierre Dubois

Chapter 2: “Prima la musica”: Gentry Daughters at Play in Town, Country, and Continent, 1815-1825

Kelly M. McDonald

Chapter 3: Stage Fright: Female Musicians Crossing Musical Borders in Thicknesse’s The School for Fashion and Burney’s The Wanderer

Danielle Grover

Part II: Women and the Market in Music

Chapter 4: Women on the Title Page: Celebrity Endorsement of Musical Scores

Penelope Cave

Chapter 5: The Lady’s Choice: Women and the Purchase of Music through Subscription

Simon D. I. Fleming

Chapter 6: Female Musical Entrepreneurship in the Eighteenth Century

Alison C. DeSimone

Part III: Women as Critics and Fans

Chapter 7: Women as Quiet Critics

Jane Girdham

Chapter 8: Femininity and Foreignness in George Colman’s Farce, The Musical Lady

Leslie Ritchie

Chapter 9: Georgian Fangirls: Women and Castrati in Eighteenth-Century London

Jeffrey A. Nigro

Part IV: Women and the Bardic Tradition

Chapter 10: Anna Gordon and the Ballad Collectors

Ruth Perry

Chapter 11: Antiquaries, Female Harpists, and the Survival of the Bardic Tradition

Devon R. Nelson

Part V: Revisiting the Age of Austen

Chapter 12: “That Ecstatic Delight”: Gender and Performance in Adaptations of Sense and Sensibility

Gayle Magee

Chapter 13: “Here’s harmony!”: Music and Gender in Kirke Mechem’s Pride & Prejudice (2019) and Jonathan Dove’s Mansfield Park (2011)

Juliette Wells

Bibliography

Notes on Contributors

Index

Praise for Women and Music in the Age of Austen (included on Bucknell University Press’s website):

“Women and Music in the Age of Austen offers an expansive, lively, colourful view of the gendered musical practices of the eighteenth century and the Romantic period. These essays enrich our knowledge of the musical world of Jane Austen and Frances Burney while shining a spotlight on little-known female performers, critics, composers, consumers, collectors, fans, and musical entrepreneurs of the preceding decades.” ~Angela Esterhammer, author of Print and Performance in the 1820s: Improvisation, Speculation, Identity

“Finding inspiration in a broad range of sources, the volume reflects on women and their musical activities in Georgian England. A focus on Jane Austen and her novels moves in and out of the picture, amplified and receding against historical figures known and unknown. Through these essays by musically-informed literary scholars and musicologists, readers get a sense of the possibilities and desires of women engaged with music over a historical period that brackets the life of our beloved Jane.” ~Maribeth Clark, coeditor of Musicology and Dance: Historical and Critical Perspectives

“Music was important to Jane Austen, as her novels and letters attest, and women played a hitherto undervalued part in the musical world of her time. This sparkling and substantial collection of interdisciplinary essays illuminates Austen’s fiction and her age in many original and surprising ways.” ~Peter Sabor, coeditor of Jane Austen’s Manuscript Works

Preview the book on books.google.com., which pretty much allows readers to access EACH chapter!

My chapter, “‘Prima la musica,’ Gentry Daughters at Play,” deals with Emma Smith (1801-1876) and her sisters during the years of their musical education. Augusta Smith (1799-1836) was perhaps the most precociously talented woman – playing several instruments, a singer, and a musician with the ability to sight-read scores and improvise. Emma herself is the Smith “family historian” whom I follow – her letters and especially her diaries allow us in the 21-century to glimpse the life of young gentry daughters during the Regency, the prime years of Jane Austen’s publications AND their later dissemination (after Austen’s untimely death in 1817). The musical life of younger – middle – daughter, Fanny Smith (1803-1871), especially gives clues as to how daughters were introduced into society – first in the Country (around the home estate) and then in London. Fanny, for instance, lamented later in life that she never learned to READ MUSIC. Obviously, an “accomplishment” that she herself eschewed. This helps to prove how much responsibility each “student” took over her education – and also the musical leanings of certain siblings, although musicality certainly ran in families, as evidenced by those the Smiths met during the decade of 1815 to 1825.

Waterloo not only brought the Napoleonic Wars to an end, Waterloo opened the flood gates to the travellers who scoured the battleground for souvenirs, then moved east (France) and south (Italy) for a taste of culture and, especially, MUSIC.

To give readers a TASTE of the Smiths’ time in Italy, touched upon in “‘Prima la musica,’ Gentry Daughters at Play,” as an addition or furthering of knowledge, I suggest my online article, discussed in the blog post “Augusta in Italy,” entitled “Forget Me Not: Sealing Friendships from Italy 1823-1827“: presented on Academia.edu.

Women and Music in the Age of Austen is available from the usual retailers in hardcover, paperback, and ebook.

Jane Austen’s Wardrobe (book review)

Hilary Davidson’s research into Regency-era fashion, specifically that related to Jane Austen, gets the royal treatment in her second book Jane Austen’s Wardrobe (published like her first, Dress in the Age of Jane Austen, by Yale University Press). Profusely-illustrated, Jane Austen’s Wardrobe deals with items that Austen wrote about in her correspondence; as well, it presents extant “Austen” items. One item is already known to general audiences through Davidson’s early article on Austen’s Silk Pelisse. Davidson pulls inspiration from letters, matching text with accompanying images drawn from portraits, textile collections, and her own photography, reflecting her broad knowledge of the period. The more readers of Austen’s fiction might learn about the minutiae presented in her correspondence, the more these materials will gain in popularity as important tools to a greater understanding of both Austen the Woman and Austen the Writer. Davidson’s book is seminal in furthering knowledge of this author and the era in which she lived, an especially important aspect as the 250th anniversary of Austen’s birth approaches in 2025.

The stylish and beautiful presentation of Jane Austen’s Wardrobe admits a feast for the eyes. Generously sprinkled with the contemporary fashion illustrations of Nicholas Heideloff (always a joy to behold), Davidson’s opinions and arguments are brought forward with accompanying illustrations and, especially useful, photographs of garment construction and textile swatches, which allow readers to delve behind the surface of the manikin-draped garments. Even the choice of heavier matt paper as opposed to the glossy pages of most illustration-rich books felt a “plus” upon first opening Jane Austen’s Wardrobe, providing a pleasurably tactile book to handle and read.

The heart of the book, of course, is Davidson’s intellectual contribution – be it about a day dress, a pair of shoes, an embroidered gift, underwear, or jewelry.

Grabbing random “garments” from the wardrobe, for greater examination:

“1808” brings up a clothing concern from Letter 57 (dated 7 Oct 1808). Specifically, Mrs. Austen’s dying “her old silk pelisse,” which has been “picked … to pieces” prior to the dye process. The refashioned item will become a black gown suitable for mourning. This letter is most enlightening, in that Austen mentions the names of three dyers: Mr. Wren, Mr. Chambers, and Mr. Floor. As Davidson notes, Floor has, because of this letter, come down to us as someone who cost Austen money by providing back to her dyed fabric that fell to “pieces” and “divided with a Touch”. From these scant Austen comments, Davidson fashions a brief tutorial on the realities and necessities of the era’s dye process and its harsh (and unstable) chemical composition. A truism that must be considered by those attentive to Regency fashion’s materiality, Davidson points out the problems encountered when giving over a piece (either fabric length or an actual gown) to dyers: Maybe it fares well; but maybe it does not.

Letter 15 (dated 24 December 1798) brings out of the closet a “Course Spot Muslin Gown.” The portrait facing the text, by Thomas Beach, provides readers with a simple presentation of just such a gown to which Austen’s letter refers: A scoop-neck with ruffle and a belt under the bust; generous sleeves; a beautifully-rendered fabric surface. Delving deeper, by turning the page, readers encounter a detailed close-up of real fabric and a second illustrating the hidden construction of a muslin skirt. Both are photographs by the author. The letter quotation brings out that Austen’s constricted clothing budget caused her to feel “ashamed of half my present stock [of clothing]” and that “I even blush at the sight of the wardrobe which contains them.” An appropriate moment of sisterly comedy that perhaps lent itself to the title of this very book. Austen’s letter also shows the predetermined end result for that “course spot muslin gown”: She tells her sister that it will end up as a “petticoat very soon.” We are thus shown a moment in the life of Jane Austen, who, from the date, could have been in the midst of writing a draft of “Catherine”.

Davidson goes on to describe the “pre-eminence” of muslin – which will have readers turning to Northanger Abbey. She outlines the story behind Britain’s struggle to produce its own muslins, in competition with the famed Indian muslins, the import of which had been banned in an early attempt at protectionism. To provide readers with opportunities for “further reading,” Davidson’s footnote points to Clair Hughes’ Dressed in Fiction (2005) and its section on muslin and Northanger Abbey, and then Lauren Miskins’ article on muslin and consumer consumption. Readers may then turn towards the back of the book for a specific discussion of petticoats, in which we discover that, “The word ’petticoat’ covered a range of garments for Regency women.” This is illustrated with photographs of what could be taken as more modern “slips.” The cotton petticoat, with its openwork hem, could easily be taken for a gown were it not identified as a “petticoat” (dating to 1815-1825; in the Hopkins Collection, London). It is here that Davidson lays out the multiple meanings that the simple word “petticoat” took on, including (in or by 1814) that of “any skirt, even those with bodices,” this based on Austen’s reference to “‘coloured petticoats with braces’ as fashionable outerwear” (letter 106, dated 2 September 1814, to Martha Lloyd).

A 1799 sample concentrates on Jane Austen having worn “my Green shoes last night.” The illustrations highlight, from the Victoria and Albert Museum collection, a gorgeous 1790s pair of nicely-decorated green shoes, the vamp ornamentation reminiscent (to this reader) of peacock feathers (which of course also brings the famous Peacock edition of Pride and Prejudice to mind). More likely the decoration is “floral,” but the illustrations show how open to interpretation a fetching pair of shoes that peeped beneath a flowing skirt still can be today.

Davidson’s interpretation clarifies the design of the woman’s shoe, including the period’s low heel, so much more comfortable-looking than the statuesque heels and diamond buckles of the earlier Georgian period. From “columnar” dresses that showcased the more “natural form,” shoes likewise were fashioned to be not only highly fashionable but also unlikely to make the wearer “‘trip and totter.’” Further explication discusses the shape of the toe, from pointed, to rounded, to “blunt or square.” Fashion-changes we today are cognizant of in our own shoe-closets. The 18th and early 19th century never felt so close as in this discussion of this most utilitarian item: one’s footwear. The low “throat” of the 1798 shoe, which facilitated ease of slipping the shoe on, unfortunately also presented the wearer with an ease of “slip off” while dancing. It is therefore a useful tidbit that is presented next: a Regency shoe from 1800 with ribbon lacing. This section also includes a small photograph of Marianne Knight’s (Austen’s niece) silk evening shoes from the 1820s, in the collection of Jane Austen’s House Museum, Chawton.

Also from the Chawton collection is an embroidered handkerchief belonging to Cassandra Austen, her initials inset within a small satin-stitch wreath of flowers. The embroidery was done by her sister, Jane Austen. The inclusion of a handkerchief brings up not only the work the Austen sisters accomplished, but also the use of them by these women – including Austen’s satirical comment to her niece Anna Lefroy that she “took two Pocket handkerchiefs [to the theater], but had very little occasion for either.” No tears from laughter or moving sentiment. Davidson clues in readers that handkerchiefs would also have been used as a handy washable cloth (in an era of no-running-water), and could also be utilized for “carrying and wrapping.” Of course, personally embroidered, such made the perfect gift. This is attested to by Austen’s touching wedding gift to Catherine Bigg in 1808, which she paired with an appropriate verse. Davidson wisely notes that, while Austen’s hands were busily at work, her mind could be busy at plotting and writing.

It is from such small and intimate glimpses of Jane Austen as daughter, sister, friend, author that brings out the value in Davidson’s Jane Austen’s Wardrobe. Insight into her wardrobe, in both senses of the word – as clothing and as her personal item of furniture – allows readers to share a new understanding of the times and background important to the novels and family letters. Fully cited and with a bibliography, the “Recommended Reading” and “Glossary” are additional useful components; as well, the Index allows for quick reference.

Highly recommended for all Austen enthusiasts.

Four full inkwells.

Mother and Child Reunion

This story is so FANTASTIC that I simply have to blog about it, so you can read it for yourself.

“A combination of detective work, art expertise, … a few strokes of serendipity” and GOOGLE (of all things…; but I’ve been there myself!) has led researchers to locate – and reunite! – a family portrait, from which the mother had been divided from the father and son.

“The baroque family portrait by Flemish painter Cornelis de Vos was painted in 1626, but the large double portrait housed at The Nivaagaard Collection [Denmark] only featured a father holding his young son’s hand. In the lower right hand corner of the portrait a dress could be seen, indicating that the boy’s mother must have been “cropped” out at some point. That theory turned out to be right.”

The story that I read appears at the website, NICE NEWS. I invite you to check out – and perhaps even subscribe so that you, too, have only Nice News appearing daily in your inbox.

In addition to Nice News, which includes a 10-minute video, see:

- The Art Newspaper

- UPI

- National Public Radio (NPR, which has a close-up of the mother’s hand – the telltale CLUE!)

- NPR’s 1st story

The HUNT is on to finding the family’s identity.

New Book Sightings

From time to time I search for new books that are nearing publication. Recently, I noticed that costume historian Hilary Davidson has a new book, Jane Austen’s Wardrobe, due out on September 12, 2023:

“What did Jane Austen wear?

“Hilary Davidson delves into the clothing of one of the world’s great authors, providing unique and intimate insight into her everyday life and material world.”

Davidson’s earlier book, Dress in the Age of Jane Austen, was – despite its minuscule, grey typeface – a fine introduction to clothing of the era. It will be interesting to see how this history is built up, especially given the slim evidence that remains of extant clothing (more, of course, mentioned in the Austen Letters). For sure, there will be plenty of illustrations! (I find the cover illustration enchanting.) Davidson has published on a recreation of Austen’s Pelisse, which allowed us to see the tallish, slim person Austen must have been when the pelisse was new.

Published, like Dress in the Age of Austen, by Yale University Press; page count is advertised as 240 pages. $35 / £25.

A sampling of page images at Yale’s UK site. If you “click” on an image, but then right-click and open it in its own window, you can make the image large enough to read the text.

If you wish, I’ll start you off:

https://yale-university-press-uk.imgix.net/interiors/9780300263602.in01.jpg?auto=format&h=648

Copy & paste and you’ll see the table of contents. CHANGE the “in01” to “02” and you’ll see the next image (section opening for GOWNS); and so on. There are 10 images, which include several “articles,” if you wish to delve into the text itself. (IS it the same grey type as the last book??)

Chapters are broken down into:

- Gowns

- Spencers, Pelisses, Outer Garments

- Hats, Caps, Bonnets

- Shawls, Tippets, Cloaks, Shoes (love the shoe images!)

- Gloves, Fans, Flowers, Trims, Handkerchiefs

- Necklaces (those crosses!), Rings (THAT ring), Bracelets (you know the one)

- Undergarments, nightwear

For some reason, Yale’s US site has “share” buttons (facebook, twitter, etc) below the cover image instead of book page images!

***

I will take this opportunity to speak to the December 2023 release of the book in which I have a chapter that focuses on the Smith Family of Suttons and 6 Portland Place, London:

Women and Music in the Age of Austen, edited by Linda Zionkowski with Miriam F. Hart, delves into the varied world of musicians, amateur artists, and connoisseurs. The book “highlights the central role women played in musical performance, composition, reception, and representation, and analyzes its formative and lasting effect on Georgian culture.”

Published by Bucknell University Press, it is distributed by Rutgers University Press. The Table of Contents is listed at the link.

“‘Prima la musica’: Gentry Daughters at Play in Town, Country, and Continent, 1815-1825,” the title of which translates to “First the Music,” looks at the decade in which the Smith sisters, especially Augusta and Emma, were learning music, were seeing London performances and befriending London artists (and, often, taking lessons from these London “masters”), then broadening their knowledge of music and languages (take note, Mr. Darcy!) with a year-long tour of the Continent, especially during the winter they spent in Italy. I certainly believe the Smiths’ musical trajectory was a typical and familiar one among the gentry who yearly moved to London for “the Season.” Austen peeked into this milieu in Sense and Sensibility, when Elinor and Marianne go to London as guests of Mrs. Jennings.

Contributors (in addition to the editors) include:

I. Representing the Female Performer

- Pierre Dubois

- Kelly M. McDonald

- Danielle Grover

II. Women and the Market in Music

- Penelope Cave

- Simon D.I. Fleming

- Alison C. DeSimone

III. Women as Critics and Fans

- Jane Girdham

- Leslie Ritchie

- Jeffrey A. Nigro

IV. Women and the Bardic Tradition

- Ruth Perry

- Devon R. Nelson

- Gayle Mcgee

- Juliette Wells

Scheduled release date is December 15, 2023. It has an Amazon page. 272 pages; hardcover, paperback, and ebook.

GREAT “thanks” for the invitation to contribute (back in 2019, I believe it was); and heartfelt thanks to the editors (especially Linda Zionkowski), who made the process run so smoothly – and who provided FABULOUSLY USEFUL feedback during several stages of writing. I hope you, the audience, enjoy the results of everyone’s efforts!

Thanks to JASNA-Vermont

A quick post to say “thank you” to JASNA-Vermont for inviting me to speak on Jane Austen’s Sense & Sensibility. Yesterday (4 June 2023) was GREAT FUN – it’s been so long since I got to talk, in person, with people interested in All Things Austen!

Special thanks to Temple Sinai (South Burlington, VT) for hosting the event. And to Marcia, Hope, Heather, and (especially) Mary Ellen for our in-person gathering.

I share with you, dear readers, my gift — The World of Jane Austen puzzle.

I ate dinner after returning home yesterday, but I was SO INTENT upon finding a large board that I used to use as a lap-desk but especially for putting puzzles together. This was something I had as a kid — I really think it was the illustrated “board” to a Fisher-Price toy, but it LONG AGO lost its illustration. Still, my memory would NOT LET IT GO until I located it. Alas, it’s in a “toy box” (yes, I still have that childhood item), which has things stacked on top – so I’ve not taken it out yet, but I’ve touched it and know it’s there. Cannot WAIT to start the puzzle. I actually remember seeing this, last year, when at the JASNA AGM in Victoria (British Columbia). For, of course, I haunted several bookstores, and one shop had tons of PUZZLES. Thank you, JASNA-Vermont for the gift, as well as the opportunity to SHARE.

4 June 2023: Sense & Sensibility (upcoming talk)

Join JASNA-VERMONT on Sunday, 4 June 2023 –

“A House Divided? How the ‘Sister Arts’ Define the Dashwood Sisters” is my topic, which examines how ART and MUSIC affect our perceptions of Jane Austen’s Elinor and Marianne Dashwood.

We meet in the community room at Temple Sinai (500 Swift ST) in South Burlington, VT, 2-4 PM.

Everyday Fashion in Found Photographs (book)

Do you shop in “Antique Stores” – and see (sometimes…) tons of “homeless” old photographs?

Do you see old photographs pop on the screen in your eBay searches, even when you searched for something completely different?

Old cartes des visites are TINY. I purchased one of Admiral Sir Michael Seymour (the son, 1802-1887). It measures about 2.5 by 3.75 inches (depending if the backing is included) – about the SIZE of a CREDIT CARD.

So I know what author Lisa Hodgkins has been collecting – and now she shares her collection and superior knowledge of what she sees in these mini portraits with us average readers!

Everyday Fashion in Found Photographs: American Women of the Late Nineteenth Century, is Lisa Hodgkin’s tour de force. It’s new to me so I will reserve a fuller review for later, but I am caught up in the photographs and the written text wherein Hodgkins explains how the American Civil War era affected women’s clothing, even the textiles available (or homemade, when required). I love reading descriptions of known items like “the cage crinoline,” the “Zouave jacket,” and the ubiquitous mourning jewelry. Even when the terms are new to me, the STYLES will be recognized by (if nothing else) the film Gone With the Wind, for instance.

What, you might ask, is a blog about the Regency Era in England doing “gushing” over old photographs from the era of the American Civil War (and beyond)??

“Children!” is my one-word reply.

I recently found a drawing, done circa 1880s, that I believe is Mary Gosling / Lady Smith’s younger daughter, Augusta Cure. Augusta was the wife of the Rev. Lawrence Capel Cure, long-term clergyman for Abbess Roding (appears also as Abbotts Roothing), county Essex. NOW I am obsessed with identifying the sitters in two images of young ladies by the same artist – identified as C.M. Moffatt. I believe I know WHO the sitters were. Of course, those two drawings are LONG sold.

BUT what grabs my attention even more are the photographs of the 1850s and 1860s (a few beyond those dates too) of the parents — Emma Austen Leigh’s siblings — and children (Emma’s nieces and nephews; and the in-laws that came along in those decades).

In reading Hodgkins’ text, and seeing through her eyes the small details of the skirt-shapes or “military”-inspired stripes, I am SEEING these FAMILY photographs, too, with new eyes. Not just searching their faces, but also admiring details of their clothing. Three albums exist (plus loose images), and the albums typically DATE as well as IDENTIFY their sitters. So date is not as important – plus the family sitters are known to me by birth-year, so some can be dated through the presumed age of the sitter.

I also recognized, LONG AFTER, that the Jane Seymour, represented in a plethora of photographs, was NOT the daughter of Maria and John Culme-Seymour, but the same-named niece, daughter of John’s brother William, who had emigrated to Australia. This little Jane Seymour came to her father’s homeland as a child! She lived with Dora and Arthur Currie. The link is to a blog post in which I discuss this annoying mistake. Annoying because, while it is GREAT having a photograph (a number of them), I still do not have a photograph of Jane (Culme) Seymour! The ONLY child of Emma’s siblings I can’t say “I know what she looked like”.

Also annoying is that I FOUND, in a faded photograph, Mary’s two daughters – Mimi (Mary Charlotte) and Augusta Elizabeth, in the 1850s, but – until the drawing surfaced – I wasn’t QUITE sure I knew which sister was which. Although, my gut instinct has pretty much been confirmed. The sister standing is surely Mimi, while the sister seated is the younger sister, Augusta. I blogged about this *FIND* and provide the link to that post. I updated the link to UCLA for that image, but (finally) post it below. Their image is No. 143.

As you can see, it’s faint — but it is a photograph, glued into an album, by the pioneering photographer, Alfred Capel Cure, in 1854. “Fixing” images was problematic in the early days. It is better than no image whatsoever. Now, thanks to Lisa Hodgkins, I wish I could see the clothing and jewelry with the clarity that the two faces (especially Augusta’s) that meet our gaze.

Everyday Fashion in Found Photographs: American Women of the Late Nineteenth Century is a fabulous book, the lessons of which help even someone like me with women who lived “across the pond,” and whose war was the Crimean War instead of the American Civil War. HIGHLY recommended, so matter your interests in 19th century fashion.

[click to enlarge]

[click to enlarge]